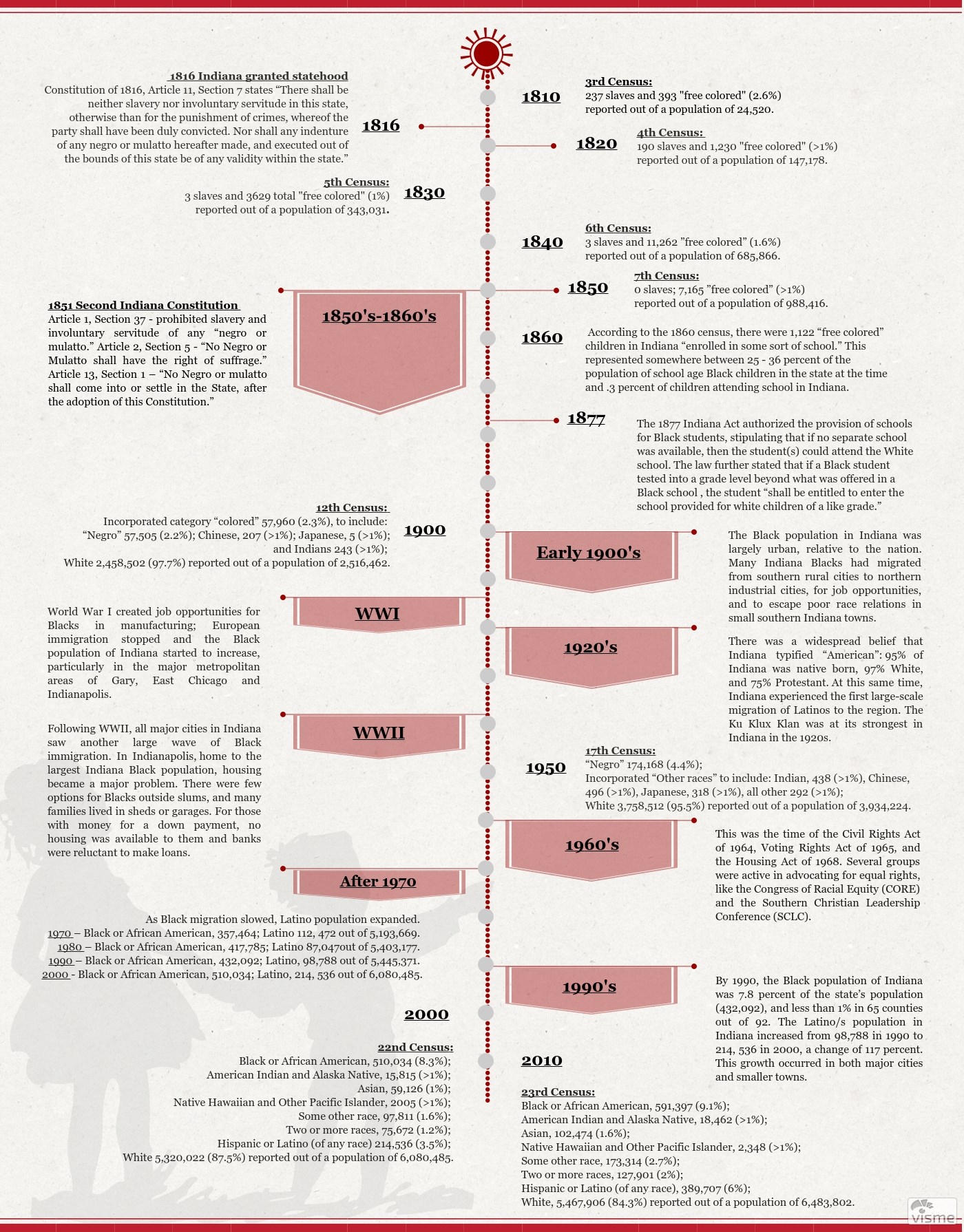

In 1816 Indiana joined the Union as the 19th state1. Like the United States as a whole, the history of Blacks in Indiana began in slavery and involuntary servitude. Prior to statehood, the 1810 Census reported 237 slaves and 393 “free colored” persons in Indiana’s population of 24,520; many of the latter were not free, but indentured servants (Thornbrough, 1957; U.S. Census Office, 1853, Table 1). Though Indiana’s Constitution of 1816, Article 11 prohibited the practice of slavery and “involuntary servitude,” it took decades for these practices to end. The 1840 Census reported three slaves and 11,262 “free colored” persons out of a population of 685,866; no slaves were reported by the 1850 Census (U.S. Census Office, 1853, Table 1).

In the mid-1800s, Black individuals who settled in the “free” state of Indiana fell into one of three categories: free persons who chose to come to Indiana; emancipated slaves; and, escaped slaves (Thornbrough, 1957). In Indiana, most Black settlements could be found along Underground Railroad routes. Although there were several routes through Indiana, Siebert (1898) describes three main, well-traveled routes (through Richmond, Madison, and Rensselaer) but with most settlements found along Indiana’s southern border. By 1860, Indianapolis—crossed by both the middle and southern routes of the Underground Railroad—had one of the largest Black populations in the state.

Between 1850 and 1860, however, there was a decline in the Black population due to both the state’s 1851 constitutional exclusionary act (“No Negro or mulatto shall come into or settle in the State, after the adoption of this Constitution.”) and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required escaped slaves be returned to their “masters” if captured. The 1881 Revised Statutes of Indiana formally removed the exclusionary act from the constitution (Rev. Stat. Ind. 1881; see also Gray, 1994).

By 1900, Black persons had migrated from Indiana’s southern rural cities to northern industrial cities. The migration was mostly due to job opportunities, but small southern Indiana towns had the “tradition of ‘sunset’ or ‘sundown laws,’ enforced not only by public opinion but also by sheriffs … that decreed blacks could not settle in the town or stay overnight” (Thornbrough & Ruegamer, 2000, p. 3; see also Thornbrough, 1957). In 1900, Indianapolis continued to have the state’s largest Black population with 15,391 of a total population of 169,164, or 9.4 percent (Thornbrough & Ruegamer, 2000).

Beginning in 1914, the demands of World War I (and the drastic decline of European immigration) created manufacturing job opportunities for the Black community in Indiana (Thornbrough & Ruegamer, 2000). Indiana’s Black population especially in the major metropolitan areas of Gary, East Chicago, and Indianapolis (Bodenhamer & Shepard, 2006).

In 1920, despite this growth in the Black population, 97 percent of Indiana’s population were White (with 95 percent being native born). There was a widespread belief that Indiana typified “American” (Madison, 1982). The Ku Klux Klan was at its strongest in Indiana in the 1920s (Thornbrough, 1994). While there was little violence during this time period, in 1930, in the City of Marion two young Black men were lynched. Shortly thereafter, Indiana’s state legislature passed a law requiring the sheriff’s dismissal in a county where a lynching has taken place. Following this passage, there were no further such occurrences in the state (Madison, 1982).

During and after World War II, all major cities in Indiana saw another large wave of Black migration. In Indianapolis, still home to the state’s largest Black population, housing became a major problem. Outside slums, there were few housing options for the Black population; many families lived in sheds or garages. Even for those Black families and individuals that could afford a down payment, housing was made unavailable and banks were reluctant to make loans. Similar lack of fit housing and unfair housing practices existed in Fort Wayne, South Bend, and Evansville (Thornbrough & Ruegamer, 2000).

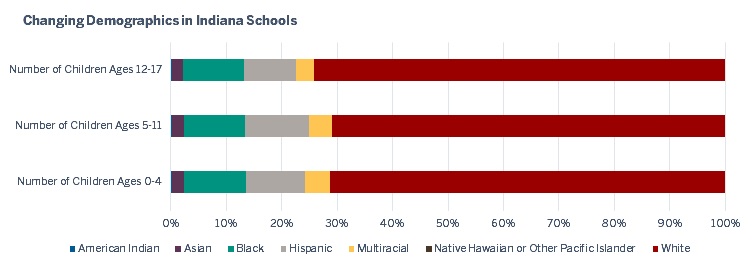

During the second half of the 20th century, Indiana’s White families moved into suburban areas while Blacks became a more concentrated part of city populations; a trend not unchanged today. (See the data visualization’s tab, Geography of segregation; select “school” level, and, for category, first select “Black” and then select “White.”) By 1970, Black migration to Indiana slowed. The 1970 Census reported 357,464 Blacks (or African Americans) out of 5,193,669 total population, or 6.8 percent (U.S. Census Bureau, 1973, Volume 1, Part 16, Table 19). The 1980 Census reported 417,785 Blacks (or African Americans) out of 5,403,177 total population, or 7.7 percent (U.S. Census Bureau, 1982, Volume 1, Part 16, Table 18). In the 2000 Census, Indiana’s Black residents represented 8.3 percent (510,034 out of 6,080,485) of the population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2002, Summary population and housing characteristics, Table 3). Black populations continue to be more concentrated in urban areas; for instance, in 1990, the Black population was 7.8 percent of the state’s population, but in 65 counties out 92, the Black population was less than 1 percent (Thornbrough & Ruegamer, 2000). In the 2010 Census, there were 591,397 Black residents reported (9.1 percent) out of a population of 6,483,802 (U.S. Census Bureau (2012), Summary population and housing characteristics, CPH-1-16, Indiana, Table 3).

The CEEP data visualization demonstrates that, over the past decade, there have been few concentration changes in Indiana’s Black population. Of note, using the Exposure rates tab, the decade trends suggest that, as compared to 2006, today’s average Black student is more likely to attend school with other Black students, Hispanic students, or students on the free and reduced lunch program, but less likely to attend school with White students.

1 Before the appearance of Europeans in North America, the land which is now Indiana was home to several different Native American cultures. Termed as Indiana’s “prehistoric” cultures, little documentation of these peoples exists; for a summary of what information is known, see Kellar’s work, An Introduction to the Prehistory of Indiana (1983). The Native American cultures (who later co-existed with French, English, and American settlers) are termed “historic”; for this history, see, for example, Indiana History: A Book of Readings (1994), edited by Ralph Gray.

First, it is important to acknowledge that, prior to the 1970 Census, there was no direct census data gathering of the Hispanic or Latino/a population. The 1970 Census included four measures that attempted to capture what was termed the population of “Spanish speakers”— questions on birthplace, Spanish surname, “mother tongue,” and asking census participants to self-report their origin (Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central or South American, or other Spanish origin). These questions only went to a sample of the U.S. population via a long-form survey (as opposed to the short form sent to the total population) (Ennis et al., 2011; Cohn, 2010). The U.S. Census Bureau reported that, due to misinterpretation of these questions, 1970 Census data regarding “Spanish speakers” were underestimated, and overestimated, in different ways (U.S. Census, 1973b). In 1980 and 1990, the Census Bureau included Hispanic descent questions on the short form; in 2000 the term “Latino” was added and there were changes to instructions. Since the 2000 Census, the Census Bureau has worked on improving the accuracy and reliability of the race and ethnicity data (Krogstad and Cohn, 2014); it is clear, however, that early reporting on the Hispanic or Latino/a population in the U.S. is not reliable.

In the early 1900s, there were two waves of Mexican immigrant workers to the Midwest. The first, in the early 1920s, was largely due to high demand for workers in the steel industry; many of these workers settled in Gary and the Indiana Harbor section of East Chicago (Lane and Escobar, 1987). The second wave was the result of anti-Catholic provisions in the Mexican Constitution in the late 1920s, which resulted in large numbers of educated and middle class Mexican immigrants immigrating to the U.S. (Young, 2012).

Indiana is currently described as an emerging settlement state for Latino/a population (Gross et al., 2012); the state has experienced recent rapid growth but is distinct from states like California or Texas, where, historically, Latino/as have settled or immigrated in larger numbers (Suro & Tafoya, 2004).

Per the 2000 Census, Latino/as represented 3.5 percent of Indiana’s population—but that population reflected a dramatic increase of 117 percent from 1990 (from 98,788 in 1990 to 214,536 in 2000) (U.S. Census Bureau, (2002), Summary population and housing characteristics, Table 3).

In the next decade, from 2000 to 2010, the growth of the Latino/a population in Indiana was 81.7 percent; in contrast, the same growth nationwide was 43 percent. In 2010 Latino/as represented 6.0 percent of Indiana’s population (U.S. Census Bureau, (2012), Summary population and housing characteristics, CPH-1-16, Indiana. Table 3).

Although many of Indiana’s Latino/a population originated from Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, or other Central or South American countries, Levinson et al. (2007) estimate that half of Indiana’s Latino/a population originally settled in other states in the South or Southwest before moving to Indiana for economic or social reasons. In keeping with national trends (Suro and Tafoya, 2004), these newcomers did not settle just in large cities, but dispersed throughout Indiana to settle in smaller cities and towns. CEEP’s data visualization demonstrates this movement of the Latino/a population throughout Indiana. (See the data visualization’s tab, Geography of segregation; select “Hispanic” as the student category and select “county” as the level of detail; the brighter orange dots indicate a higher percentage of Latinos dispersed in both rural and urban areas.)

This summary focuses on the key legislation and case law impacting segregation1 in the public schools from Indiana’s induction as the 19th state in 1816 until the present day. The summary also includes relevant federal legislation and case law where applicable.

Prior to Brown v. Board of Education

Admitted into the Union in 1816, Indiana’s early social and educational practices resulted in de jure (by law) and de facto (by practice) segregation for well over a century. Yet the first state constitution mentioned race in only three instances: Article III established that only White men were enumerated for purposes of districting for the General Assembly; Article VI gave voting rights to White males over twenty-one; and ,“Negroes, Mulattoes and Indians” are mentioned in Article VII which excludes these populations from serving in the militia. Two additional sections implicitly address race-related policies: Article XI, Section 7 outlawed slavery and involuntary servitude and, in regards to education, Article IX established that it would be the responsibility of the state to provide for “a general system of education … wherein tuition would be gratis and equally open to all” (Ind. Const. of 1816, Art. IX, § 2).

Early Indiana school laws excluded Black students implicitly or explicitly. For instance, a school law of 1837 (passed in 1838), which incorporated congressional townships and provided for the establishment of common public schools, stated, “That the White inhabitants of each congressional township” be counted as inhabitants (1837 Ind. Acts, p. 509). Black inhabitants were not counted and did not “constitute the body corporate,” and Black children were thereby implicitly excluded from common public schools. In 1843, language was added that made it clear that Indiana’s public schools were “open and free to all the White children resident within the district, over five and under twenty-one years of age” (1843 Ind. Acts, p. 320). Shortly after the addition of this language, the Indiana Supreme Court ruled that Black students could not attend public schools even if they paid tuition. The decision in Lewis v. Henley and Others (1850) referred to the exclusionary language of the 1843 law; the Court noted “It may aid us in answering this question, to inquire, why the legislature has excluded them from attending at the public charge … black children were deemed unfit associates of white, as school companions” (p. 334). Despite these circumstances, in the early 1800s, some of Indiana’s relatively few Black children were able to attend private schools run by Black community members, religious groups, or philanthropic organizations.

In 1851, Indiana amended its constitution to guarantee a free and uniform system of common schools to be funded by taxes but did not address race (Ind. Const., Art. 8, § 182). Language in state statutes then became more explicitly exclusive. New school law language addressing the provision of common schools in 1853 and 1855 specifically excluded “negroes [and] mulattoes” from these benefits (1853, Ind. Acts, p. 124; 1855, p. 161). According to the 1860 U.S. Census, there were 1,122 “free colored” children in Indiana “enrolled in some sort of school” (Thornbrough, 1957, p. 181), representing between 25 percent and 36 percent of the population of school-age Black children in the state at the time and 0.3 percent of children attending school in Indiana2 (U.S. Census Bureau, 1864, Table 1; Thornbrough, 1957).

By 1869, the Indiana General Assembly authorized separate but equal schools for Indiana’s Black students (Indiana Special Session Act, 1869), with the stipulation that, if there were not enough Black students in a community to warrant a separate school, the proportion of local funding for these students should be used to provide some other means of education. The Special Session Act (1869) stated, “But if there are not a sufficient number within reasonable distance to be thus consolidated, the trustee or trustees shall provide other such means of education for said children” (p. 41). James Smart, Indiana’s State Superintendent of Instruction (1876), defined “other means” in his biennial report: “In some localities, it results in sending the colored children to a private school, in others, giving the children books to read … but in many, it results in nothing” (p. 23). He went on to note that this was “deplorable” and “unwise” and called on the law to be amended to support integrated schools where necessary.

Soon after, the language of the school law of 1877 (Ind. Acts, Art. VII, § 4496) legally opened the door for integration, though it did not encourage this process in word or meaning. The new law authorized the provision of schools for Black students, stipulating that if no separate school was available, then the student(s) could attend the White school. The law further stated that if a Black student tested into a grade level beyond what was offered in a Black school (for instance, a student tested into high school where there was not a Black high school), the student “shall be entitled to enter the school provided for white children of a like grade” (1877, Ind. Acts, Art. VII, § 4496, p. 124). According to Thornbrough, however, “The question of separate or mixed schools was left almost entirely to the local authorities” (1957, p. 329), which resulted in inconsistency in implementation. In addition, the law did not specify that schools needed to be equal, and there were great inequities in the quality of schooling and school accommodations made available to Black students (Thornbrough, 1957). By the end of the 19th century, the U.S. Supreme Court had legitimized “equal but separate” public services vis-à-vis Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). Language in the decision specifically pointed to schooling: “The most common instance of this is connected with the establishment of separate schools for white and colored children, which have been held to be a valid exercise of the legislative power even by courts of states where the political rights of the colored race have been longest and most earnestly enforced” (p. 544).

According to Thornbrough, the first half of the 20th century saw increased segregation but primarily through “custom and prejudice, rather than law,” as manifested in residential and employment segregation (2000, p. 6). The 1897 and 1901 compulsory attendance laws that required that all children between the ages of seven and fourteen attend school were silent on race (Ind. Acts, 1897; 1901).

By the mid-1940s, however, state and local policy makers were creating a stream of policies against segregation in Indiana. For instance, in 1946, the Gary School Board issued a non-discrimination policy protecting students in the school district they lived in and within the school they attended—a policy largely in name only, as most segregation continued due to de facto residential housing choices and practices (Beilke, 2011; Cohen, 1986, 2002). In 1945 the Indiana General Assembly called for a voluntary end to workplace discrimination (1945, Ind. Acts, Chapter 325). Soon after, prompted by pressure from officers of the state and local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and emboldened by a new Democratic governor and House of Representatives (Beilke, 2011; Thornbrough & Ruegamer, 2000), the General Assembly put a legal end to segregation in 1949 with an act that established “the public policy of the State of Indiana to provide, furnish and make available equal, non-segregated, non-discriminatory educational facilities for all regardless of race, creed, or color” (1949 Ind. Acts, p. 604); this legislation made Indiana one of the last non-slave states to statutorily remove segregation (Kluger, 1976).

The timeline established by the 1949 Indiana law gave school districts until 1954 to end segregated schools, coinciding with the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education that overturned the “equal but separate” doctrine of Plessy (1896). In the unanimous opinion, Chief Justice Warren wrote, “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated … are by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment” (Brown v. Board of Education, 1954, p. 495).

Post-Brown v. Board of Education

Indiana in the 1960s

As was the case across the country, the Brown decision and Indiana’s own precursor in 1949 did little to motivate action. As a result, the U.S. Supreme Court decided in Brown II that states that were to implement remedies to segregation with “all deliberate speed” also lacked specific enforcement mechanisms for implementation (Brown v. Board of Education II, 1955, p. 301). Eventually, however, frustrated parents and organizations in Indiana who felt desegregation efforts were not moving forward turned to the courts.

One of the early cases in Indiana was against the School City of Gary (Bell v. School City of Gary, 1963). The NAACP argued that the Gary school district had an obligation to provide a racially integrated school system with equal facilities. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit instead affirmed an earlier district court ruling that the racial make-up of Gary schools was due to residential neighborhood patterns. As such, the lack of integration was not a deliberate attempt by the school board to segregate students; the ruling stated that desegregation did not mean “there must be intermingling of the races in all school districts … [but only that] they must not be prevented from intermingling” (Bell v. School City of Gary, 1963, p. 213, emphasis added; see also Beilke, 2011; Cohen, 2002; Reynolds, 1998).

Additional lawsuits demonstrate early implementation struggles after Brown and Brown II. In Copeland v. South Bend Community School Corporation (1967), families of Black children attending the Linden School in South Bend sued to stop the construction of a new (replacement) school in a predominantly Black neighborhood, seeking a more racially balanced location; the suit was put on hold when the roof collapsed in the existing school building. Although U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit found the school to be structurally sound and the case resumed, the case was subsequently settled when the school corporation agreed to seek better racial balance (Reynolds, 1998).

Also in 1967, the federal district court investigated allegations that Kokomo schools were illegally segregated based on existing enrollment and staffing, as well as district plans to build a new school in a primarily White area despite the “deteriorating conditions” of other schools that served more Black students (“NAACP scores a victory,” 1967). Although the case was settled, the presiding judge did order the closing of two predominantly Black elementary schools (“NAACP scores a victory,” 1967; Reynolds, 1998; Thornbrough & Ruegamer, 2000).

In 1970, plaintiffs in Muncie, Indiana were concerned with the location of a new high school planned in an “all-White area” (Banks v. Muncie Community Schools, 1970, p. 293); at the time, there were two high schools in the district, both with approximately 13 percent Black populations. The Black community feared the location would serve to increase segregation due to its location. On this issue, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit affirmed earlier rulings in favor of the school district, stating that the “allegation that de facto segregation will result from the construction of Northwest High School is unfounded, or, at least, premature” (Banks v. Muncie Community Schools, 1970, p. 294).3

Relevant Federal Law in the 1960s and 1970s

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, federal court rulings and laws provided agencies with guidance about how they could enforce integrated schooling. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 authorized the Attorney General’s office to act if parents filed a complaint that their children were being deprived of equal protection under the law. Valid complaints that were not remedied within a reasonable amount of time could be addressed by the Justice Department at the district court level.

In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg (1971), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that busing—a traditional form of public education transportation—can be used as an appropriate remedy to achieve integration: “Bus transportation has been an integral part of the public education system for years, and … [is] a normal and accepted tool of educational policy” (p. 9, § 4). Further, the decision notes, “Desegregation plans cannot be limited to the walk-in school” (p. 30). This decision also noted that when districts became unitary, busing would end: “Neither school authorities nor district courts are constitutionally required to make year-by-year adjustments of the racial composition of student bodies once the affirmative duty to desegregate has been accomplished and racial discrimination through official action is eliminated from the system” (p. 32). The Court did also note that the language of the Civil Rights Act does not imply that the federal government can require that a district use transportation of pupils to achieve integration: “Nothing herein shall empower any official or court of the United States to issue any order seeking to achieve a racial balance in any school by requiring the transportation of pupils or students from one school to another or one school district to another in order to achieve such racial balance” (p. 17).

Milliken v. Bradley (1974) involved busing as a remedy for segregation in Detroit; unlike Swann, however, it involved not just the school district of Detroit but the surrounding suburban school districts as well, and the outcome was different. In this case, the NAACP contended that, through housing policies and district lines, official state and city policies had created and perpetuated segregated school conditions in Detroit. Although the lower courts supported an interdistrict plan that proposed busing students beyond the city limits to the surrounding suburbs to achieve more racially balanced schools, the U.S. Supreme Court found that local autonomy was “essential both to the maintenance of community concern and support for public schools” (Milliken v. Bradley, 1974, p. 741). Given that the surrounding districts had not been found in violation of Brown, the Court determined that they should not be part of the solution; this “metropolitan area remedy … [is] a wholly impermissible remedy” (p. 745).

Indiana in the 1970s and 1980s

Some Indiana lawsuits began to follow national trends of the late 1960s and early 1970s, which reflected support for integration. For instance, in 1972, Evansville-Vanderburgh School Corporation attempted to rescind its desegregation plan—one that would have more fully integrated all of the elementary schools in the system except one—in favor of a new plan that would leave over half of the elementary schools “all White, or virtually all White” while six of the 34 schools would have Black enrollment of 20 percent or higher (Martin et. al. v. Evansville-Vanderburgh School Corporation, 1972, p. 819). The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana ruled for the plaintiffs, calling on Evansville-Vanderburgh to eliminate “the last vestiges of racial segregation from its school system before January 1, 1973” (Martin et. al. v. Evansville-Vanderburgh School Corporation, 1972, p. 820).

By the 1980s, settlement in desegregation cases became more common: “Indeed, it appears that school desegregation is one of the areas in which voluntary resolution is preferable to full litigation because the spirit of cooperation inherent in good faith settlement is essential to the true long-range success of any desegregation remedy” (Armstrong v. Board of School Directors of City of Milwaukee, 1980, p. 318). In 1980, the U.S. Attorney General filed a complaint against the South Bend Community School Corporation seeking the desegregation of its schools; the consent decree between the two parties was filed the same day. The consent order set forth a desegregation plan that required that the “percentage of Black students in each high school, middle school, and regular elementary school be within 15 percentage points of the total percentage of Black students who attend all the schools in the corporation” (U.S. v. South Bend Community School Corporation, 1981, p. 7, § IV). This case faced challenges to jurisdiction and outside intervention in subsequent years (see U.S. v. South Bend Community School Corporation, 1982, 1983). In 2002, the original plan was amended and approved by the District Court and it remains in force. One change emphasizes assigning primary students at schools closest to their homes, with the stipulation that children in schools where the Black population exceeds 15 percent are permitted to transfer on a controlled choice4 basis (Schmidt, 2014). According to a 2014 South Bend school district report, “13 of the 18 primary centers meet the guidelines, all 10 of the intermediate centers, and all of the high schools meet the guidelines” (Schmidt, 2014, p. 4).

In 1986, the not-for-profit corporation Parents for Quality Education with Integration, Inc. filed a class action suit against the Fort Wayne Community Schools, claiming that the district had “failed to dismantle the dual system and acted or failed to act in such a manner as to maintain and to exacerbate conditions of segregation” (Parents for Quality Education with Integration, Inc. v. Fort Wayne Community Schools Corp., 1990, p. 5). As in South Bend, the parties agreed to settle via a consent decree, which was adopted by the U.S. District Court in 1990. The decree included a racial balance plan that relied in part on magnet schools to encourage voluntary transfers and addressed needed support such as transportation and marketing. Full compliance with the system-wide racial balance goal was described as follows: “Full compliance and performance will be deemed to exist so long as no school falls below the 10 percent Black range and no more than three schools fall into the 45 percent to 50 percent Black range” (Parents for Quality Education with Integration, Inc. v. Fort Wayne Community Schools Corp., 1990, p. 7, No. 6).

The most notable and prolonged desegregation case in Indiana, however, involved the Indianapolis Public Schools (IPS). To clearly understand this case, one must begin with the Consolidated First-Class Cities and Counties Act, known as Unigov (1969; see also Ind. Code 36-3). The act consolidated the governments of the city of Indianapolis with surrounding Marion County; a single legislative body—the City-County Council—was established in 1970.5 Many services were consolidated, including but not limited to, road maintenance, natural resource management, and public health. This consolidation served the “public purpose by allowing the consolidated city to: (A) eliminate duplicative services; (B) provide better coordinated and more uniform delivery of local governmental services; (C) provide uniform oversight and accountability for the budgets for local governmental services; and (D) allow local government services to be provided more efficiently and at a lower cost than without consolidation” (Ind. Code 36-3-1-0.3 (4)). The public schools in the city and county, however, were excluded from this merger. As historians Owen and Willbern (1985) note, any suggestion of including the schools in this plan “was a volatile issue that needed to be handled cautiously” (p. 98) to avoid any suggestion of promoting integration at the time.

At this time, however, IPS was already under scrutiny. Andrew Ramsey, the president of Indiana’s state conference of the NAACP, had written to the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare requesting an investigation into discriminatory practices in teacher assignment in Indianapolis. Under the authority of the Civil Rights Act, the U.S. Justice Department charged IPS with racial discrimination in the assignment of both students and teachers. In an attempt to avoid further prosecution, IPS announced plans to close two high schools with high proportions of Black students: Crispus Attucks and Shortridge. These schools had strong supporters in the Black community who resisted the closings. Other attempts to comply with the Justice Department to remedy the discrimination failed to satisfy the Justice Department (see, for example, Beilke, 2011; Thornbrough & Ruegamer, 2000), and in 1971, Judge Dillin found that IPS did indeed “operate a dual school system, or, put another way … [had] a deliberate policy of segregating minority (Negro) students from majority (White) students in its schools” (United States of America v. The Board of School Commissioners of the City of Indianapolis, 1971, p. 3). Judge Dillin’s detailed memorandum of decision examined racial attitudes from as early as the 1600s and addressed the history of residential segregation in the city (see United States of America v. The Board of School Commissioners of the City of Indianapolis, 1971). Ultimately, Judge Dillin ruled that the school board had “perpetuated segregation through the use of optional attendance zones … construction of new schools … transporting students … and assignment of special education classes” (p. 10). Dillin also reasoned that the Unigov decision to exclude the public schools from the consolidation was discriminatory; he proposed the use of busing into suburban districts as a remedy, but this action was delayed in a final order pending review of several legal questions. This case extended into the 1980s; some busing was introduced in the 1970s and busing to the suburbs was introduced in 1980. The order was lifted in 1998 under a transition plan (for a more complete history, see, for example, Beilke, 2011; Indianapolis Public Schools Desegregation Case Collection, 1971–1999; Thornbrough & Ruegamer, 2000).

1990–Present

One more recent desegregation case of relevance in Indiana is actually federal; in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 (2007), the U.S. Supreme Court found that the two student assignment plans at issue relied too heavily on race and were therefore unconstitutional. Although the Court held that student body diversity was a compelling state interest, it also found that the two districts involved in the case, Louisville and Seattle, had not demonstrated that their use of race was narrowly tailored; race was being used as the sole factor rather than part of a broader ideal of diversity. Pursuant to this decision, the U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Department of Education (2011) issued guidance citing the benefits of racially diverse schools and the risks of racially isolated schools. The guidance encouraged race-neutral or generalized race-based approaches and outlined steps for schools to pursue these models in order to increase student body diversity.

Summary

As can be seen clearly, from its entry into the Union, Indiana legislators used legal means to limit the access of non-White students to education; over time, discrimination evolved from more implicit means to more explicit statements. Since the 1949 Indiana School Law and Brown at the federal level in 1954, however, various legal authorities have held that segregated schools deprive Black and other non-White students the equal protection of the law under the Fourteenth Amendment. Since the late 1960s, Indiana case law has addressed segregation in the context of issues including racial balance in integrated schools, residential housing segregation, location of new facilities, and voluntary and involuntary transfer solutions. The most recent Supreme Court case on this issue, Parents Involved, made the consideration of race in student assignment plans difficult and encouraged districts to devise race-neutral solutions to promote racial diversity in schools. Given the demographic patterns demonstrated in CEEP’s data visualization, policy makers must continue to explore solutions that will address current segregation concerns.

1 As this summary demonstrates, the law focused heavily on denying rights to Black citizens in Indiana, although at times the term White was used, which does imply that other minorities were also excluded.

2 The 1860 Census (U.S. Census Bureau, 1864, Table 1) provided counts for “free colored” children between the ages of 5 and under 10, 10 and under 15, and 15 and under 20 in the state of Indiana. Using the 5–under 20 range, the percentage of Black students attending was 25 percent of that total. Using 5–under 15, the percentage was 36 percent of that total. It is reasonable to assume it was somewhere between these two values.

3 Part of this lawsuit also alleged discrimination at Southside, one of the existing high schools. This school featured a flag resembling the Confederate flag, its sports teams were the “Rebels,” and the homecoming queen was named the “Southern Belle.” On this issue, the court found that although “the symbols complained of are offensive and that good policy would dictate their removal, we find no evidence in the record before us that a constitutional violation has occurred” (p. 299).

4 Controlled choice attempts to allow parental choice while maintaining the racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic balance of the schools by using specific constraints (Ehlers, Hafalir, Yenmez, & Yildirim, 2014); in this instance, “Clusters have been identified to permit Black students to transfer to schools that have too few Black students, or, conversely, to permit Non-Black students to transfer to schools that have too few Non-Black students” (Schmidt, p. 9).

5 It is of note that this governmental reorganization was not approved by referendum, despite the “prevailing practice in the United States [which] requires that any major (and often minor) metropolitan governmental reorganizations … be approved by referendum” (Owen & Willbern, 1985, p. xx).